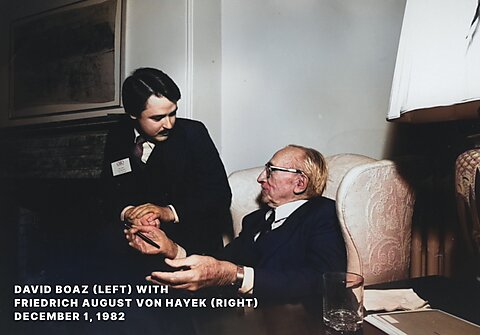

On December 1, 1982, F. A. Hayek became Cato’s first Distinguished Lecturer. Cato had supported his work for several years, and he was later named a Distinguished Senior Fellow — an honor to be sure, but not quite up to the level of his 1974 Nobel Prize.

Hayek’s life spanned the 20th century, from 1899 to 1992. In his youth he thought he saw liberalism dying in nationalism and war. Thanks partly to his own efforts, in his old age he was heartened by the revival of free‐market liberalism. John Cassidy wrote in the New Yorker that “on the biggest issue of all, the vitality of capitalism, he was vindicated to such an extent that it is hardly an exaggeration to refer to the twentieth century as the Hayek century.”

Back in 2010 the New York Times said that the Tea Party “has reached back to dusty bookshelves for long‐dormant ideas. It has resurrected once‐obscure texts by dead writers [such as] Friedrich Hayek’s “Road to Serfdom” (1944).” I responded at the time,

So that’s, you know, “long‐dormant ideas” like those of F. A. Hayek, the winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, who met with President Reagan at the White House, whose book The Constitution of Liberty was declared by Margaret Thatcher “This is what we believe,” who was described by Milton Friedman as “the most important social thinker of the 20th century” and by White House economic adviser Lawrence H. Summers as the author of “the single most important thing to learn from an economics course today,” who is the hero of The Commanding Heights, the book and PBS series by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw, and whose book The Road to Serfdom has never gone out of print and has sold 100,000 copies this year.

On the occasion of Hayek’s 100th birthday, Tom G. Palmer summed up some of his intellectual contributions:

Hayek may have made his greatest contribution to the fight against socialism and totalitarianism with his best‐selling 1944 book, The Road to Serfdom. In it, Hayek warned that state control of the economy was incompatible with personal and political freedom and that statism set in motion a process whereby “the worst get on top.”

But not only did Hayek show that socialism is incompatible with liberty, he showed that it is incompatible with rationality, with prosperity, with civilization itself. In the absence of private property, there is no market. In the absence of a market, there are no prices. And in the absence of prices, there is no means of determining the best way to solve problems of social coordination, no way to know which of two courses of action is the least costly, no way of acting rationally. Hayek elaborated the insights of the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, whose 1922 book Socialism offered a brilliant refutation of the dreams of socialist planners. In his later work, Hayek showed how prices established in free markets work to bring about social coordination. His essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” published in the American Economic Review in 1945 and reprinted hundreds of times since, is essential to understanding how markets work.

But Hayek was more than an economist. As I’ve written before, he also published impressive works on political theory and psychology. He’s like Marx, only right. Tom Palmer noted:

Building on his insights into how order emerges “spontaneously” from free markets, Hayek turned his attention after the war to the moral and political foundations of free societies. The Austrian‐born British subject dedicated his instant classic The Constitution of Liberty “To the unknown civilization that is growing in America.” Hayek had great hopes for America, precisely because he appreciated the profound role played in American popular culture by a commitment to liberty and limited government. While most intellectuals praised state control and planning, Hayek understood that a free society has to be open to the unanticipated, the unplanned, the unknown. As he noted in The Constitution of Liberty, “Freedom granted only when it is known beforehand that its effects will be beneficial is not freedom.” The freedom that matters is not the “freedom” of the rulers or of the majority to regulate and control social development, but the freedom of the individual person to live his own life as he chooses. The freedom of the individual to break old molds, to create new things, and to test new paths is the mark of a progressive society: “If we proceed on the assumption that only the exercises of freedom that the majority will practice are important, we would be certain to create a stagnant society with all the characteristics of unfreedom.”

Reagan and Thatcher may have admired Hayek, but he always insisted that he was a liberal, not a conservative. He titled the postscript to The Constitution of Liberty “Why I Am Not a Conservative.” He pointed out that the conservative “has no political principles which enable him to work with people whose moral values differ from his own for a political order in which both can obey their convictions. It is the recognition of such principles that permits the coexistence of different sets of values that makes it possible to build a peaceful society with a minimum of force. The acceptance of such principles means that we agree to tolerate much that we dislike.” He wanted to be part of “the party of life, the party that favors free growth and spontaneous evolution.” And I recall an interview in a French magazine in the 1980s, which I can’t find online, in which he was asked if he was part of the “new right,” and he quipped, “Je suis agnostique et divorcé.”

Hayek lived long enough to see the rise and fall of fascism, national socialism, and Soviet communism. In the years since Hayek’s death economic freedom around the world has been increasing (until a hopefully temporary dip during the Covid pandemic), and liberal values such as human rights, the rule of law, equal freedom under law, and free access to information have spread to new areas. But today liberalism is under challenge from such disparate yet symbiotic ideologies as resurgent leftism, right‐wing authoritarian populism, and radical political Islamism. I am optimistic because I think that once people get a taste of freedom and prosperity, they want to keep it. The challenge for Hayekian liberals is to help people understand that freedom and prosperity depend on liberal values, the values explored and defended in his many books and articles.

Hayek came to Cato once more, for a small lunch. I have a picture from that event that I especially like because it looks like it’s just myself and Hayek at the table. Except for the dozen or so wine and water glasses of tablemates who weren’t in the camera shot.

“Exclusive Interview with F. A. Hayek,” Cato Policy Report, vol. 6, no. 3, May/June 1984.

“An Interview With F. A. Hayek,” Cato Policy Report, vol. 5, no. 2, February 1983.