Daniel Ellsberg died on June 16, and he remains one of the nation’s most prominent whistleblowers who leaked secret government information to the public. Upon his death the general consensus among the writers of memorials for Ellsberg was that he was right to leak government secrets. As the editorial board at The Orange County Register recently put it, he was “a true American hero.”

They’re right about Ellsberg. During the Vietnam War, through his release of the so-called Pentagon Papers in 1971, Ellsberg made public a large trove of secret government documents that exposed many of the Federal government’s lies about its involvement throughout Indochina. Much of the information applied to the Johnson Administration which had been lying about the war to both the public and the Congress. Naturally, the release of this information, which smashed the Federal government’s credibility on foreign policy, also called into question countless claims about the Nixon Administration. Nixon, of course, had already authorized an illegal and secret bombing campaign in Cambodia in 1969.

At the time, the response to Ellsberg’s deeds was hardly one of universal acclaim. Yet, over time, criticism has waned and Ellsberg’s critics have been exposed for what they were: knee-jerk defenders of a regime devoted to war crimes and crimes against the Bill of Rights.

In fact, it has become so difficult to criticize Ellsberg that defenders of today’s regime have had to devise ways to claim that Ellsberg’s leaks were heroic, but the leaks by more recent whistleblowers—such as Julian Assange and Edward Snowden—have been traitorous. The fact that Ellsberg himself always supported leakers like Snowden and Assange is studiously ignored.

Yet, what was true for leakers in 1971 remains true today: it is heroic to expose the lies of governments, and those who seek to jail truthtellers are the real criminals who choose to protect state power at the expense of freedom and basic human rights.

The Original Response to Ellsberg’s Leak

It does not require any courage or independent thinking to support Daniel Ellsberg in 2023. To do so is to do what is already accepted and popular. This is why journalists almost universally support Ellsberg today. It’s easy.

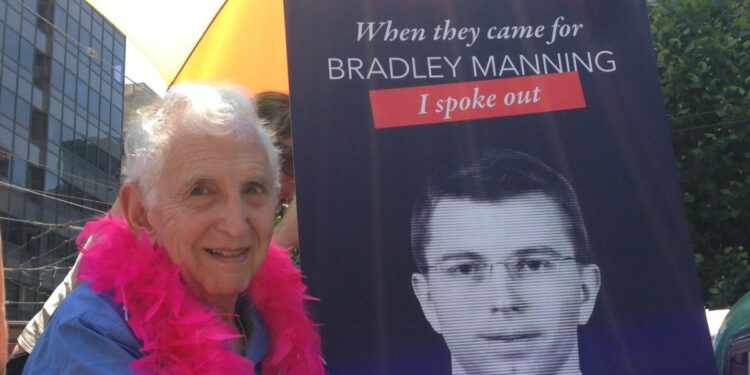

Yet, to support modern-day Ellsbergs—such as Assange, Snowden, Reality Winner, Chelsea Manning, and Jack Texeira—requires some degree of independent thought, skepticism, and disregard for the regime. This is why so few journalists in the corporate media support these modern-day leakers. To do so might endanger journalists’ positions with the organs of power within mainstream media. Moreover, most corporate journalists are firmly on the side of the regime. They have no interest whatsoever in undermining it.

Indeed, many journalists at the time of the release of the Pentagon Papers condemned Ellsberg. For example, at the 1971 meeting of the Associated Press Managing Editors Association a speaker insisted that approval of Ellsberg is akin to approval of any “pamphleteer” who publishes “a plan of a secret submarine or a list of foreign agents abroad, obtained from any peddler of secrets.” The editors of TIME magazine, meanwhile, reminded readers that the federal government ought to use the “remedy” of prosecuting whistleblowers if publishing secrets might “endanger national security.” The editors fail to mention that the federal government itself gets to determine what the amorphous phrase “national security” actually means.

Politicians, of course, freely attacked Ellsberg with that term that is forever a favored refuge of the simple-minded: “traitor.” The Nixon Administration prosecuted him under the Espionage Act of 1917. Ellsberg himself suspected he would spend the rest of his life in jail, but he escaped conviction thanks to the administrative incompetence of Nixon’s “Plumbers.” The Nixon Administration had already violated so many of Ellsberg’s basic procedural rights in the lead up to the trial that no court would side with the administration. Ultimately, however, it must be noted that the Supreme Court took no action to meaningfully limit the Espionage Act. The Court took the easy way out in spite of the fact that the Act has always been unconstitutional, immoral, and contrary to basic property rights. As David Gordon has summed it up:

The [Espionage Act] blatantly violated the text of the Constitution. The First Amendment states that “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech”; and as Justice Hugo Black liked to say, “‘no law’ means ‘no law’.” Congress had earlier violated the First Amendment with the Sedition Act of 1798; but along with the Alien Act of the same year, it was repudiated by Thomas Jefferson and was generally regarded as a disaster. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court said that the Espionage Act was constitutional.

In other words, Ellsberg managed to walk free on a technicality, but the threat of prosecution against other whistleblowers, who have done the same thing as Ellsberg, remains.

The Myth of the “Good” Leaker

The fact that media opinion and public opinion generally sides with Ellsberg has done little to shield modern-day leakers from both public condemnation and legal prosecution.

Modern supporters of Ellsberg who also condemn men like Snowden and Assange attempt to justify this contradiction by creating narratives like the myth of the “good leaker.” Kevin Gosztola has shown this tendency in how many who favor prosecuting Snowden and Texeira have attempted to claim that Ellsberg was a “responsible” leaker who held back information that might have been damaging to US national security. Yet, Gosztola shows this was not actually the case. Ellsberg did indeed expose the name of at least one clandestine CIA officer. Moreover, Ellsberg himself has noted that when he did withhold information from his leaks, it was not to protect the regime or its agents. Rather, Ellsberg feared releasing that data might hurt efforts to negotiate an end to the war. Ellsberg did not care “if the names of U.S. intelligence sources were exposed.”

Ellsberg was also aware that defenders of the US security state used his case to discredit modern-day leakers and manipulate the narrative. Gosztola notes:

Ellsberg said the pundit class has used him as a “foil” against any “new revelations” of systematic government abuses of power. They have claimed certain leaks were different than his leaks to make it easier to discredit people who took great risks to reveal the truth.

Why the Regime Loves Secrets

Naturally, it is necessary to create the myth that Ellsberg is “good” and Assange, et al, are “bad” so as the get around the pesky reality that most everyone today accepts it was for the best that many Vietnam-era lies were exposed. At the time, of course, this was hardly self-evident to millions of Americans who had been sufficiently propagandized into the idea that the federal government ought to be able to do more or less whatever it wants in the name of “national security.”

This attitude certainly continues today, and it is this lazy deference to the prerogatives of the federal security state that allows federal agents and their enablers to keep alive efforts to arrest Assange and Snowden so the CIA and FBI can take their pound of flesh.

This attitude, of course, is thoroughly incompatible with the idea of self-government and the rule of law. In the years immediately following the end of the Cold War, even many Conservatives began to see the damage the Cold War had done to basic American freedoms in this respect. Thus, Sam Francis would write in 1992:

A self-governing people generally abhors secrecy in government and rightly distrusts it. The only way, then, in which those intent upon . . . the expansion of their power over other peoples, can succeed is by diminishing the degree of self-government in their own society. They must persuade the self-governing people that there is too much self-government going around, that the people themselves simply are not smart enough or well-informed enough to deserve much say in such complicated matters as foreign policy. . . . We hear it . . . every time an American President intones that “politics stop at the water’s edge.” Of course, politics do not stop at the water’s edge unless we as a people are willing to surrender a vast amount of control over what the government does in military, foreign, economic, and intelligence affairs.

Governments like to keep secrets because it is politically expedient. It helps smooth the ways for more wars, and larger wars. It helps ensure the taxpayer gravy train keeps flowing, and that the taxpayers are untroubled by real facts about government lies and government crimes. Ellsberg—and other heroes like Assange, Snowden, and Manning—undermine the regime by telling the truth. This is why modern journalists and politicians hate them.