On May 3, 2023, the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted a rule to update stock buyback disclosures, igniting the debate over the economics of stock buybacks once again.

The rule would require certain stock issuers to provide disclosures of daily repurchase activity on a quarterly or semi‐annual basis. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce is vexed by the narrative surrounding this decision and has threatened to pursue litigation. They posit that disincentivizing buybacks will, “hurt the retirement savings of millions of Americans and result in slower economic growth—hurting the wages of working Americans.”

The Chamber is right to be wary of this anti‐buyback drumbeat. Stock repurchases occur when public companies buy shares of their own stock—distributing money to shareholders in exchange for reclaiming company ownership. As I have noted before, critics claim they come at the expense of productive investment and that they enrich executives by manipulating the earnings per‐share ratio. Combined, these effects are said to represent capitalism’s worst features: a short‐term unwillingness to invest driven by rampant executive self‐interest.

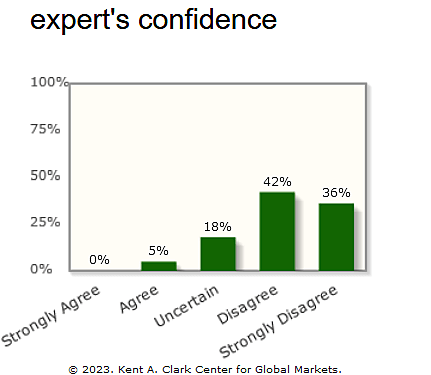

Such criticisms are misguided. When existing shareholders are compensated for their shares, these funds do not simply disappear. As my colleague Adam Michel noted earlier this year, one paper estimates that 95 percent of funds used for stock buybacks are reinvested elsewhere in the economy. What’s more, if critics are right that firms engaging in buybacks are leaving lucrative investment opportunities on the table, we’d expect the long‐run share price and earnings per share to be lower after buybacks. A recent poll conducted by Chicago Booth’s Kent A. Clark Center for Global Markets demonstrates that 40 top financial economists are baffled by anti‐buyback hysteria too. The survey asked if respondents agreed that:

Large‐scale stock buybacks by public corporations provide short‐term rewards for shareholders and senior executives at the expense of potentially higher‐return corporate investments.

When weighted for expert confidence, just 5 percent agreed, while 42 percent disagreed and 36 percent strongly disagreed. John Campbell from Harvard, for example, stated, “It is not true that keeping profits inside corporations is necessarily the highest‐value use of those funds. Corporations should pass profits back to shareholders, potentially for investment elsewhere, unless they have unusually attractive investment opportunities.”

The survey later asked whether the experts agreed that:

The proposed higher tax on corporate stock buybacks would generate a substantial increase in corporate investment.

Again, just 6 percent agreed, whereas 43 percent of respondents strongly disagreed, 31 percent disagreed, and 21 percent were uncertain. Michael Roberts of Wharton added that even “if it does it is more likely that that investment is lower quality.”

The political narrative about buybacks therefore continues to be completely at odds with the views of expert financial economists.