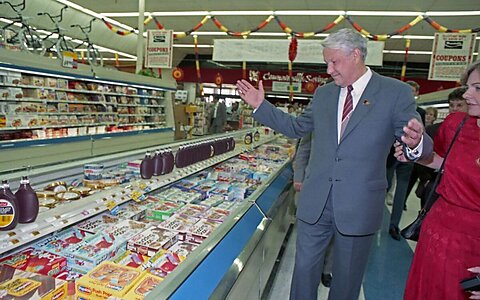

Thirty‐four years ago tomorrow, Boris Yeltsin — then a newly elected member of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union — visited NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, where he toured the U.S. government facility and the various technologies therein. But it’s a brief, impromptu visit to a nearby grocery store that may very well have changed world history.

Yeltsin, who’d two years later become the first freely elected leader of Russia, roamed the aisles of the relatively small Randall’s market that day and was astonished at the variety and affordability of the products on display. According to various reports, this visit — not the one to NASA — catalyzed Yeltsin’s exit from the Communist Party and his abandonment of the Soviet economic model. His 2007 New York Times obituary tells the tale:

During a visit to the United States in 1989 he became more convinced than ever that Russia had been ruinously damaged by its centralized, state‐run economic system, where people stood in long lines to buy the most basic needs of life and more often than not found the shelves bare. He was overwhelmed by what he saw at a Houston supermarket, by the kaleidoscopic variety of meats and vegetables available to ordinary Americans.

Leon Aron, quoting a Yeltsin associate, wrote in his biography, “Yeltsin, A Revolutionary Life”…: “For a long time, on the plane to Miami, he sat motionless, his head in his hands. ‘What have they done to our poor people?’ he said after a long silence.” He added, “On his return to Moscow, Yeltsin would confess the pain he had felt after the Houston excursion: the ‘pain for all of us, for our country so rich, so talented and so exhausted by incessant experiments.’ ”

He wrote that Mr. Yeltsin added, “I think we have committed a crime against our people by making their standard of living so incomparably lower than that of the Americans.” An aide, Lev Sukhanov was reported to have said that it was at that moment that “the last vestige of Bolshevism collapsed” inside his boss.

My Cato colleague Sophia Bagley and I recall this wonderful story in a forthcoming essay for Cato’s new Defending Globalization project, explaining how the United States’ grocery abundance — owed in large part to globalization — fueled Yeltsin’s freezer‐side conversion and has increased further since that time. Between 1975 and 2022, for example, the number of products in an average U.S. supermarket has increased by more than three‐fold, from 8,948 products to a whopping 31,530. Not all of that increase is due to globalization, of course, but much of it is. As shown below, for example, imports of essentially every type of food have increased substantially in the decades following Yeltsin’s tour of Randall’s:

Some of these gains reflect Americans’ increasing appetites for “ethnic foods” and the related explosion of such items in American grocery stores. As I note in my first essay for the project (on the current state of globalization), these cuisines are today “so commonplace that American grocers are struggling to fit them all in the ‘ethnic food’ aisle, where buyers and sellers prefer them,” while “H Mart, a Korean American supermarket chain, has become one of the fastest‐growing retailers by specializing in foods from around the world.”

But there’s probably no bigger symbol of U.S. grocery globalization than in the produce section. Supermarkets in 1980, for example, carried an average of 100 different produce items, and the number approached approached 250 by 1993. But, even then, certain fruits and vegetables were limited to North American growing seasons, and few here had even heard of products like rambutans, lychee, or jackfruit.

A casual stroll through the same aisles today, by contrast, reveals an incredible variety, driven in large part by global trade and Americans’ globalized taste buds. According to the FDA, in fact, 55 percent of fresh fruits and 32 percent of fresh vegetables are today sourced from abroad. As Bagley and I explain in our essay, much of the expansion in international trade in food is owed to trade agreements completed in the 1990s.

In the United States, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement improved Americans’ access to warm‐weather produce grown in Mexico and certain other foods in which Canada specialized (and not just maple syrup). Globally, the 1995 World Trade Organization agreements, especially the Agreement on Agriculture, dramatically reduced global food and related trade barriers. Since then, agricultural trade has more than doubled in volume and calories. (For more on why we have these and other trade agreements, check out Simon Lester’s new Defending Globalization essay.)

Globalization has even improved our domestic food supply. For example, more than 40 percent of the steel used for canning goods is sourced globally, meaning that many canned foods, although grown domestically, would be more expensive if U.S. producers lacked access to imported materials. American farmers, meanwhile, often rely on imported fertilizer, or use export revenues to fund expansions or crop experimentation. Total U.S. food and agriculture exports hit $196 billion in 2022, almost half of which ($88 billion) went to Asia.

Sadly, the hope and optimism of Yeltsin’s Russia are today a distant memory. But his amazement that day in Houston — and the blessings of American grocery abundance — are still worth celebrating. They may have even changed the world.