Congress is scheduled to consider a major farm bill this year, which will reauthorize many U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) programs, including farm subsidies and food stamps. The legislation could cost $150 billion a year and so presents an opportunity to find budget savings and reduce the flood of red ink in Washington.

Spending reformers will have to battle the farm bill’s special interest logroll. This press release from Republicans on the Senate’s agriculture committee discusses “farmers’ priorities in the Farm Bill” and the need for “producer‐focused” legislation. But what about taxpayer priorities? And why not restraint‐focused legislation?

The top Republican on the committee, John Boozman, notes that the USDA has “over nearly 100,000 employees, 29 agencies and 4,500 locations in the U.S. and abroad.” 100,000! Boozman calls for better USDA management, but he should be asking why the bureaucracy is the size of a city.

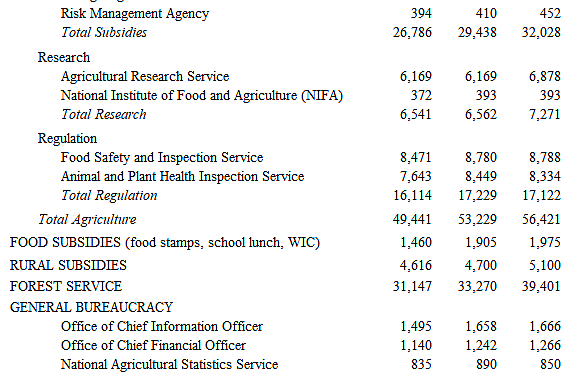

The table summarizes USDA employment, which encompasses agriculture, food subsidies, rural subsidies, and the Forest Service. The data are from page 111 here, but I’ve retitled some activities.

This USDA employee breakdown looks different than a USDA spending breakdown. For example, the USDA spends four times more on food subsidies than on agriculture, but food subsidy programs require relatively few federal workers because they are mainly administered by the states.

Some USDA activities are in‐house and some are outsourced. The Agricultural Research Service is a huge operation of more than 6,000 USDA employees in 90 locations, whereas the NIFA funds thousands of researchers at nonfederal institutions across the nation.

We can roughly divide USDA employees into three groups: (i) those supporting private interests, (ii) those supporting the broad public interest, and (iii) those in the general bureaucracy.

The first group includes employees handing out farm and food subsidies. We can downsize this workforce as we cut farm subsidies and devolve food stamp and school lunch programs to the states.

Some activities, such as the NRCS, produce both private and public benefits. The agency hands outs billions of dollars a year in subsidies to farmers but also seeks broader environmental and climate change benefits.

USDA regulatory activities ostensibly benefit the general public, but the federal regulatory process can be captured by some businesses at the expense of other businesses and consumers. Regulations can also raise costs and undermine innovation.

USDA’s research creates benefits for farmers and the general public. But most industries fund their own research even though the benefits often spill over to society more broadly. It is true that the government increasingly subsidizes research in many industries, not just agriculture, but that is a misguided direction. For the farm bill, lawmakers should explore what agricultural and food research can be shifted to the private sector.

Policymakers should downsize the USDA’s general bureaucracy. The USDA has more than 1,200 employees in two economics and one statistics office. These offices produce useful data and reports, but if the government didn’t micromanage agriculture, it wouldn’t need all that information.

The USDA runs 2,300 offices across the nation to advise and subsidize farmers. This website encourages farmers to visit their local offices because the “Farm Service Agency administers more than 50 federal farm programs nationwide. There is literally something of interest to everyone regardless of the size or type of a particular ag operation. Whether you have a row crop, livestock, diversified, niche market, small or large operation, there are likely Farm Service Agency programs for which you may qualify.”

Having federal helpers in every community in the nation is a bizarre feature of the agriculture industry. There is no system of offices across the nation with federal helpers subsidizing, say, restaurant entrepreneurs with 50 programs. Yet restaurants are very high risk, and entrepreneurs face many challenges in food preparation, worker scheduling, cash flow, and marketing.

Reformers in Congress should challenge farm bill supporters. Does the USDA need to be the size of a city? Does it make sense in our online age to fund thousands of brick‐and‐mortar offices? Shouldn’t farmers stand on their own two feet in the market economy? Shouldn’t subsidies be cut given today’s huge federal deficits?

Data Notes: The data in the table are full‐time equivalents. The figures for 2024 are proposed by the Biden administration. Within the Farm Service Agency, about 7,000 individuals are paid for by the USDA but work for nonfederal entities.